The case for adding more options, and less structure, to your life portfolio

I think a lot about the way things “blow up”.

Most of the time when something blows up, it’s because of a combination of structure and overconfidence. It happens when a person, a firm, or even an entire economy becomes overconfident, and creates a complex set of structures and obligations around what it thinks it can deliver on. Inevitably the reality of what is possible vs. what is promised becomes clear, and unwinding these structures ends up causing a lot of pain for everyone involved.

This post is about how we systematically overvalue structure and undervalue optionality, to the point where it blows up our life.

. . .

Optionality as Freedom

What is an option? Here’s the financial definition:

A financial derivative that …offers the buyer the right, but not the obligation, to buy or sell a security or other financial asset at an agreed-upon price during a certain period of time or on a specific date.

Here’s the dictionary:

The power or right of choosing.

Ha. As in my last post, the technical opacity of finance has blinded us to the simple truth. Options are about the freedom to choose.

Under this frame, optionality is not just a technical term limited to the calculation of “convex” payout functions. Rather, optionality is about value that comes from having the freedom to choose your own path.

. . .

Optionality vs Structure

I don’t just mean the ephemeral, new-wave kind of value represented by that photo, I mean real, hard value, the kind you should be willing to pay for.

Why?

Because tomorrow you might know more than you know today, and, knowing more, you might want to change the very obligations and structure that make up “your life.” In fact, the one thing we do know is that tomorrow, we will know more than we know today.

Meaning the question isn’t IF we will want to change the structure of our life, but WHERE and HOW MUCH.

. . .

The trap of structure

Looking around, I see a lot of close friends rushing to put more and more structure into their life. Some of it financial (buy this house), some of it professional (make partner at the firm), some of it familial (marriage, puppy, baby…baby), some of it even social (“this is who I play golf with on Sundays”).

Which isn’t to say any of this is wrong, bad, or unintelligent; I just worry we are as vulnerable to cognitive biases in how we build our lives as how we build our portfolios.

There’s nothing intrinsically wrong about creating structure around expectations. If we could form accurate expectations over possible future worlds and design our obligations accordingly, nothing would ever blow up. But we can’t.

Not only is the future fuzzy, not only are we generally too optimistic about our ability to deliver in the future, but we are even overconfident our ability to predict the future.

Meaning, inevitably, some of the structure we were so happy to build today ends up as a trap tomorrow, once we learn new truths and wish to change.

. . .

Blowing up your life

All this talk about blowing up structure comes from personal experience. After deciding to ‘throw it all away’ and move to San Francisco, I went through the process of unwinding a lot of my old life.

Jobs, housing, even social expectations all went out the window as I began chaotically shuttling across the country, dissembling a life ‘out east’, and building a life ‘out west.’

This process was painful, particularly for those friends that had come to expect a timely reply to emails, but it also showed me how much of my identity was tied up in the structures I gave other people to define me: structures I was now in the process of blowing up.

When you meet someone new in New York, the questions you get are What do you do? Where do you live? and sometimes Where did you go to college?

In London, the question is Where did you go to (high) school?

In San Francisco, the question is How much funding do you have?

Same question, different social context: Who are you?

All of a sudden, I didn’t have real (or simple) answers to any of those questions. Whether or not we like to talk about it, each of us feel this enormous social pressure to ‘make something of oneself.’ But the way we define what success looks like, to ourselves and to others, is usually a function of our particular slice of the world.

So while part of me liked that people had a hard time trying to “put me in a box,” I couldn’t help but reflect on how proud I had been of my particular box just months before. Pretty much classic cognitive dissonance.

To sum up, as humans we live in a world where we strive to build structure to bring meaning to our lives, for ourselves and for others. However, not only are we overconfident in our abilities, but the structure which we choose to attempt to build is a function of our particular social context.

. . .

What (if anything) does this have to do with finance?

Turns out, a lot.

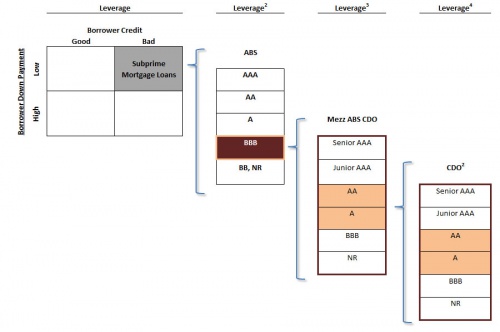

I don’t think it is a coincidence structured finance was at the heart of the securitization of US housing that almost brought down the world economy.

How do you think we get from the very good idea of allocating risk to investors that have appetite for that risk….

To this…

To this...

To this...

Simple: overconfidence and dissonance, operating on a societal level, leading to too much (financial) structure.

Overconfidence in the models and mathematicians, overconfidence that housing could “only go up,” overconfidence that someone responsible was watching the whole thing and would take away the punch bowl before it got too out of hand.

Dissonance in the form of people just not wanting to hear the bear case on housing. For example, Michael Burry, who made almost 500% by shorting the housing market in 2008, literally had to wage war with his investor base to hold onto his positions — the dissonance among his investors was that strong.

. . .

Overconfidence + structure = financial blow ups

The nice thing about financial markets is that you can actually make linkages between this conceptual stuff and the cycles we see play out over and over again.

Liquidity is just another word for optionality. If you have cash today, you have the option to spend it today on whatever you want. You also have the option to hold onto it and spend it tomorrow. In this way, liquidity today is (usually) better than liquidity tomorrow, as it provides at least as many options for what to do with your cash.

In this world, we can also think of leverage as structure. When you take out a loan, you are explicitly trading optionality today for a promise of optionality tomorrow.

Well, what do humans do when they encounter structure? Overestimate their abilities, one up the next guy, and trap themselves in a cage of their own design.

It happens to everyone. From investment firms full of Nobel economists…

…innovative energy firms…

...industrial giants...

…even credit channels…

…and disruptive industries…

…all the way up to emerging market financial systems…

…and national economic trends lasting decades.

. . .

Protecting yourself (from yourself)

So where does this leave us? How can you avoid blowing up?

- Structure —Build what you need, not what other people want, and be mindful of the obligations that come with the structure you have created, e.g., mortgages, illiquid equity stakes that come with making partner, expensive lifestyles.

- Dissonance — Think through the scenarios where those structures get you in trouble, even though those worlds are painful to imagine. Remember, we tend to discount information that comes into conflict with the interests, beliefs, or actions we have already taken.

- Optionality — Find creative ways to buy back the optionality you may have already sold, and in doing so, diversify your life against your own overconfidence.